Our life is full of forks in the road — career choices, who we form new relationships with, you name it — but the direction we chose can mean even more to our futures than ever before. If our inherent choices to move in one direction or another, commonly referred to as behavioral economics, were affecting our ability to be our best selves, it would behoove us to better understand them, right?

Below, we outline the most common behaviors we exhibit, and the ways in which they can affect our career decisions, work identities, and many other critical pivot points in our lives.

What does behavioral economics have to do with my career choices?

Before we dive into things, let’s first define behavioral economics and the context in which we’ll talk about it here. Behavioral economics helps us understand why we make certain decisions. As its name implies, behavioral economics is typically applied in financial contexts, but also has very real applications across many of our decisions.

“Yes, it is difficult to believe that we are not entirely rational in our daily decisions and actions. However, by admitting that we are biased, realizing that we should question our choices, and stepping outside of our comfort zone, we are able to open up our eyes to a whole new horizon,” Author Ahmed AlAnsari says in The Brand Dependence Model.

Let’s dig a little deeper into five common biases that can affect critical points in your daily life, such as the jobs you take or the groups of people you choose to network with.

1. Anchoring

The tendency to hold on to the first piece of information you receive when making a decision is otherwise known as anchoring. This tends to expose itself in many economic situations (e.g., how we gauge the price of items), but also in the way we communicate and generate the best ideas. Brainstorming is one area where the first good idea drops an “anchor” into the discussion and other, potentially more effective ideas, are left on the sidelines.

On the career stage, people often go into the business of their families or people they admire, because they are anchored in the belief that their success or happiness in that line of work can be replicated. This also impacts who we build meaningful relationships with. If a trusted friend or associate has a negative point of view on an individual you’ve never met, there’s a good chance you’ll be anchored in their beliefs before you can make character assessments of your own.

2. Confirmation bias

A common problem in the internet age when information is a search engine away, we can find ourselves seeking out information that confirms our existing beliefs and ignoring information that contradicts them. This is otherwise known as confirmation bias.

Confirmation bias is twisting the facts to fit your beliefs. Critical thinking is bending your beliefs to fit the facts.

— Adam Grant (@AdamMGrant) October 18, 2022

Seeking the truth is not about validating the story in your head. It's about rigorously vetting and accepting the story that matches the reality in the world.

The examples of confirmation bias in real life are vast — anything from news stations and their leanings on certain politics, to referees making more calls for the home team, to the idea that left-handed people are more creative than those that are right-handed. The list goes on.

In work context, confirmation bias can also be related to our career choices. The idea that the “grass is greener” for one job over another because reviews on Glassdoor or employee testimonials on the company’s website confirm your beliefs during the interview process. However, the best way to have an idea if an organization is best for you is to ask questions that align with your needs and beliefs.

3. Loss aversion

Unfortunately, we can feel the displeasure of losses more than the joy of gains. As Author Daniel Kahneman explains: “Loss aversion refers to the relative strength of two motives: we are driven more strongly to avoid losses than to achieve gains. A reference point is sometimes the status quo, but it can also be a goal in the future: not achieving a goal is a loss, exceeding the goal is a gain.”

The implications of loss aversion go far and wide, influencing so many of our choices, like the amount of risk we’re willing to take on a life-changing decision. For instance, we may stay in jobs longer than we may want or need to, because the idea of being unemployed for any amount of time is worse than settling for inertia.

4. Recency bias

In contrast to anchoring, people can often latch on to the last piece of information they’ve received, leading to a rash decision.

In the tech sector, it’s been argued that some recent layoffs were precipitated by organizations following in the footsteps (i.e., “copycat behavior”) of their peers rather than economics.

“The tech industry layoffs are basically an instance of social contagion, in which companies imitate what others are doing. If you look for reasons for why companies do layoffs, the reason is that everybody else is doing it. Layoffs are the result of imitative behavior and are not particularly evidence-based,” Stanford professor Jeffrey Pfeffer said in a December report.

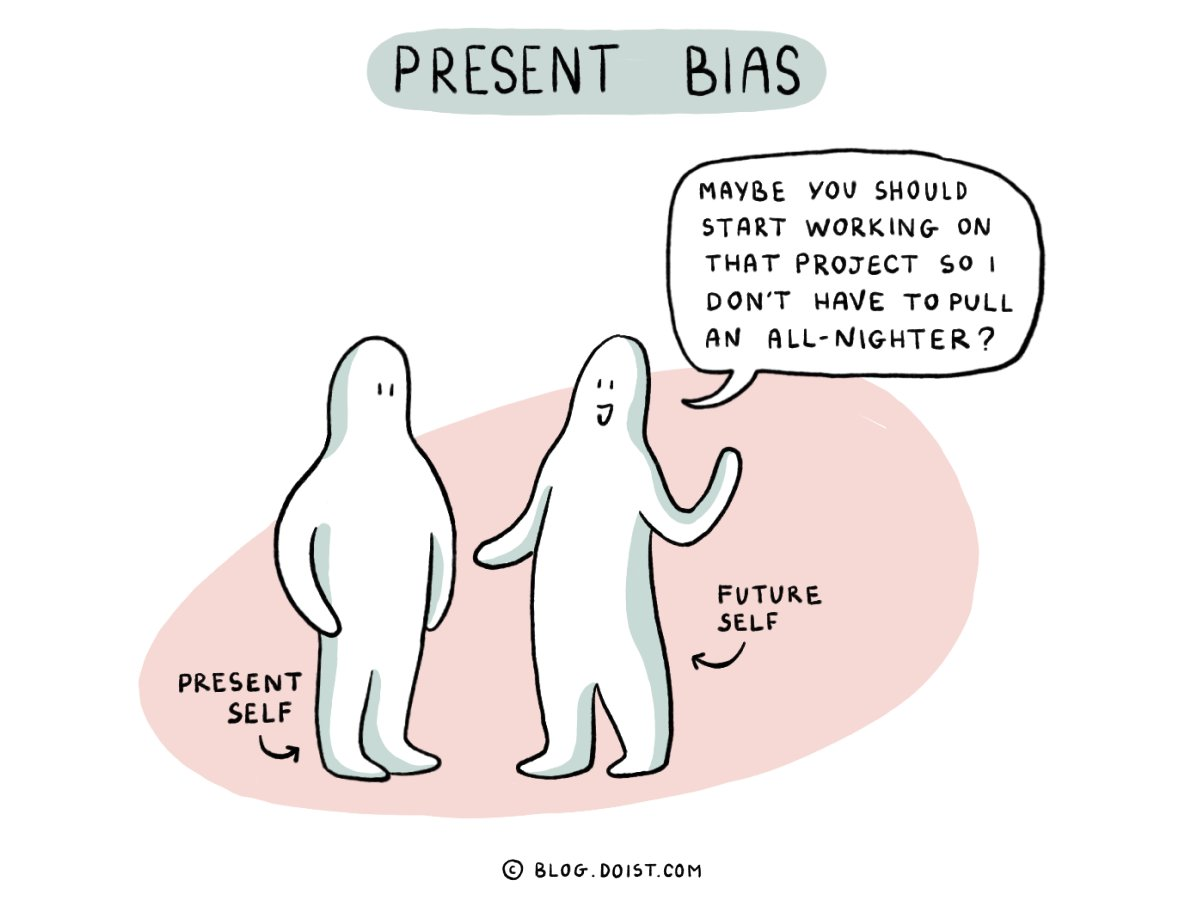

5. Present bias

Prioritizing immediate rewards over long-term benefits is what’s known as present bias. There’s inherent dangers to this approach that can affect us financially, yes, but also in what’s best for our long-term health and happiness.

The personal and professional implications of present bias behaviors are massive. On the flip side of our job example above, people can take a job that offers more money, but has a subpar culture. Taking the short-term financial benefit over the long-term stability is a risk that may end up yielding little reward to workers.